Finding a Common Language

Lukas Grellmann

Methods in a way are scientific tools and instruments employed to acquire and analyse data so as to build knowledge on a certain issue. Usually, this is something taken for granted and not questioned or challenged. For the context of our workshop, we included aspects normally not considered ‘methods’ or ‘techniques’ into our ‘tool box’, such as the situation of our work space (UdN) with its spatial qualities and social potential, the intentional mixing of different disciplines (inter- and transdisciplinary working groups) or the refusal to pre-define research questions but rather leave this to the participants (who would develop their research questions during their dérives).

Following the workshop’s objective to facilitate an international and interdisciplinary workshop on neighbourhoods, our main interest was to bring an intercultural group of researchers together and develop a common language in order to communicate. The set of methods used was supposed to help participants to jointly formulate research questions and develop appropriate research strategies according to their questions and motifs. During the workshops, methods were regarded as tools with which the research participants developed and built a deeper understanding of the composition and complexity of the urban. As neighbourhoods can be understood as small nuclei within the complex system of the urban, ‘zooming in’ to a neighbourhood can help researchers to learn on an eye-level perspective and make use of this knowledge by transferring it into the design process. Being concerned with a neighbourhood is not meant to reduce the complexity, but still provides a means to focus on a slice of the complex urban. As the participants came from a number of disciplines and professions, an important first step was to find ways of overcoming language barriers. Language here refers to more than spoken and written language as it includes the different professional languages ‘spoken’ in different disciplines and contexts.

Similarly, the participants also faced the challenge to adapt to two different research areas in a short period of time in such different urban environments in Hamburg and Cairo. The first workshop in Hamburg strongly focused on the practicing of methods and interdisciplinary group work – yet rather than discussing methods solely in theory, they were tested and tried in the ‘field’ of Veddel. The second workshop in Cairo followed up on the experiences made in Hamburg and asked the working groups to proceed with the methods they had already tested and used; they were then asked to develop them further or amend them to suit the new urban environment and its different research conditions. Therefore, methods used during the workshop have been chosen carefully in order to promote a process-oriented and interest-based research approach. Various methods were introduced and presented to the participants by experts invited; but the participants themselves also brought in methods and methodological strategies. This led to an exchange of different professional backgrounds and their respective approaches as much to a process of negotiating where which methods could come in, which methods could be combined, amended, expanded etc.

The following pages introduce and give snapshots of approaches taken during the workshop in Hamburg. In presenting them, we focus on methods and their application and demonstrate specific features that were meaningful to the workshop participants while working with these particular methods. The set of methods is neither complete nor introduced in their complexity – rather they are part of a dynamic tool box that can be adapted for particular topics, contexts and the research groups’ specific requirements and capacities. Thus, methods include ways of working together as well as communicating work in progress, such as the wall presentations, discussions over dinner and table top rounds. The common language we sought to develop turned out to reach far beyond the actual academic and scientific methods and included developing an intercultural and transdisciplinary awareness.

»Every five minutes you have another topic to talk about. They appear in an intuitive way or through a keyword or an inspiration that somebody‘s given us; even through critique or in the street or anywhere. Everybody has different ideas on how to progress in this workshop or in this project. Since we are different, we have to reach a common ground. And that’s the melting pot. How can we satisfy everybody, how can we come up with an idea that satisfies all people in the group? So this is how it’s built up. We come from different backgrounds, professions and cultures so each of us tackle what they see differently with unique eyes. We see things in a different way and this is how hard it is to progress and sometimes how useful it is. So it is a hard thing and a good thing at the same time. And this was the biggest challenge in this project: how can we work together to reach a single understanding of the neighbourhood? To advance in this project we come up with all kinds of creative ideas.«

Mohamad Abotera

Observation

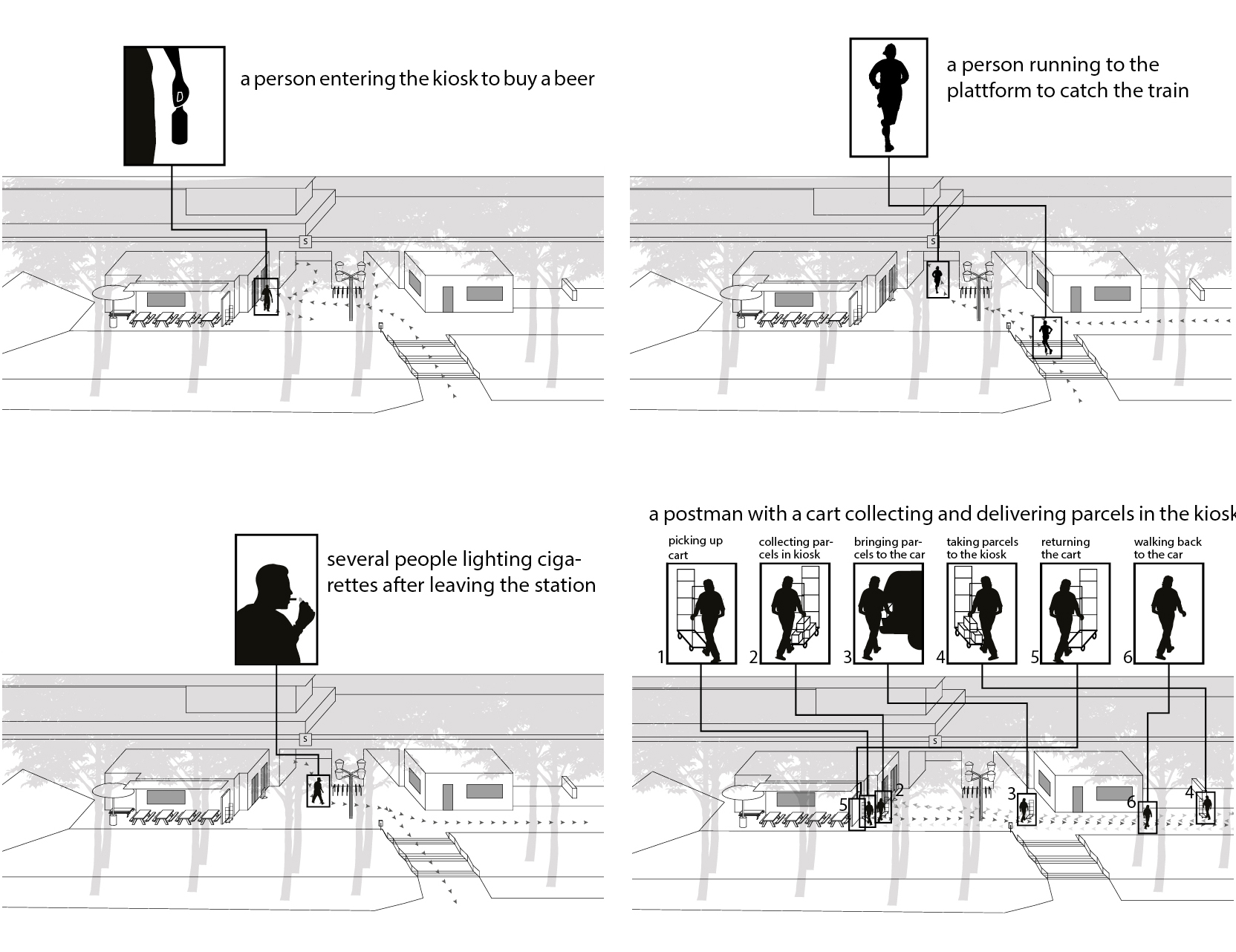

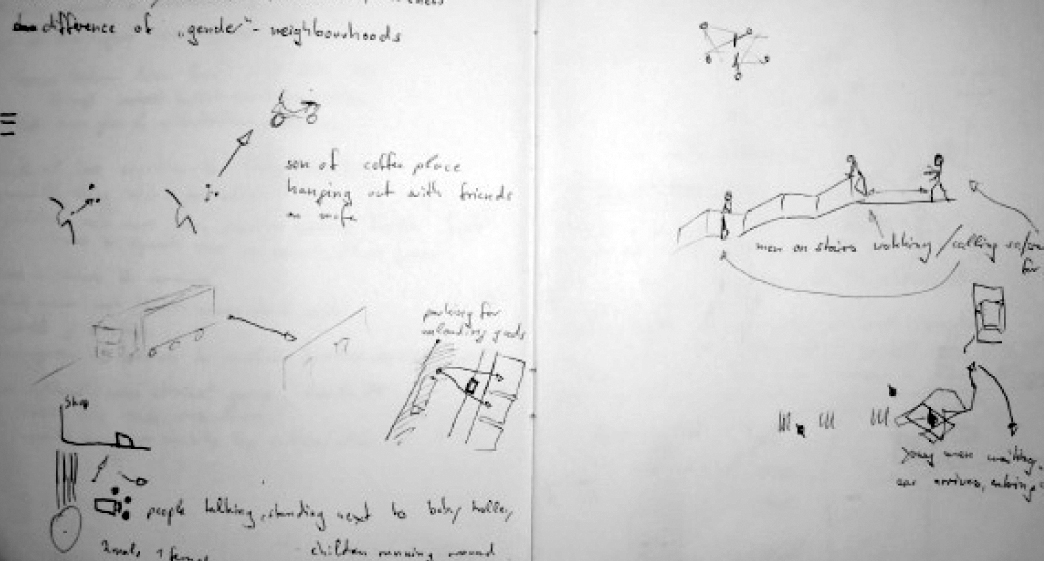

Observation helps to get a sense of a place, an initial feeling for its quality, but also serves to complement data generated through other methods, such as interviewing or mental maps. What and how we observe can either be predefined or be decided upon while observing an area. While prepared questions can help generate a sense of the area, it is equally possible to start an observation from scratch and to follow one’s interest. Observations and the subsequent thick description of what has been observed are borrowed as a method from ethnography and anthropology (e.g. Spradley 1980).

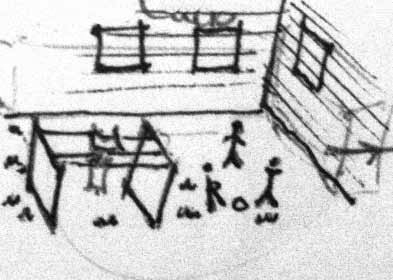

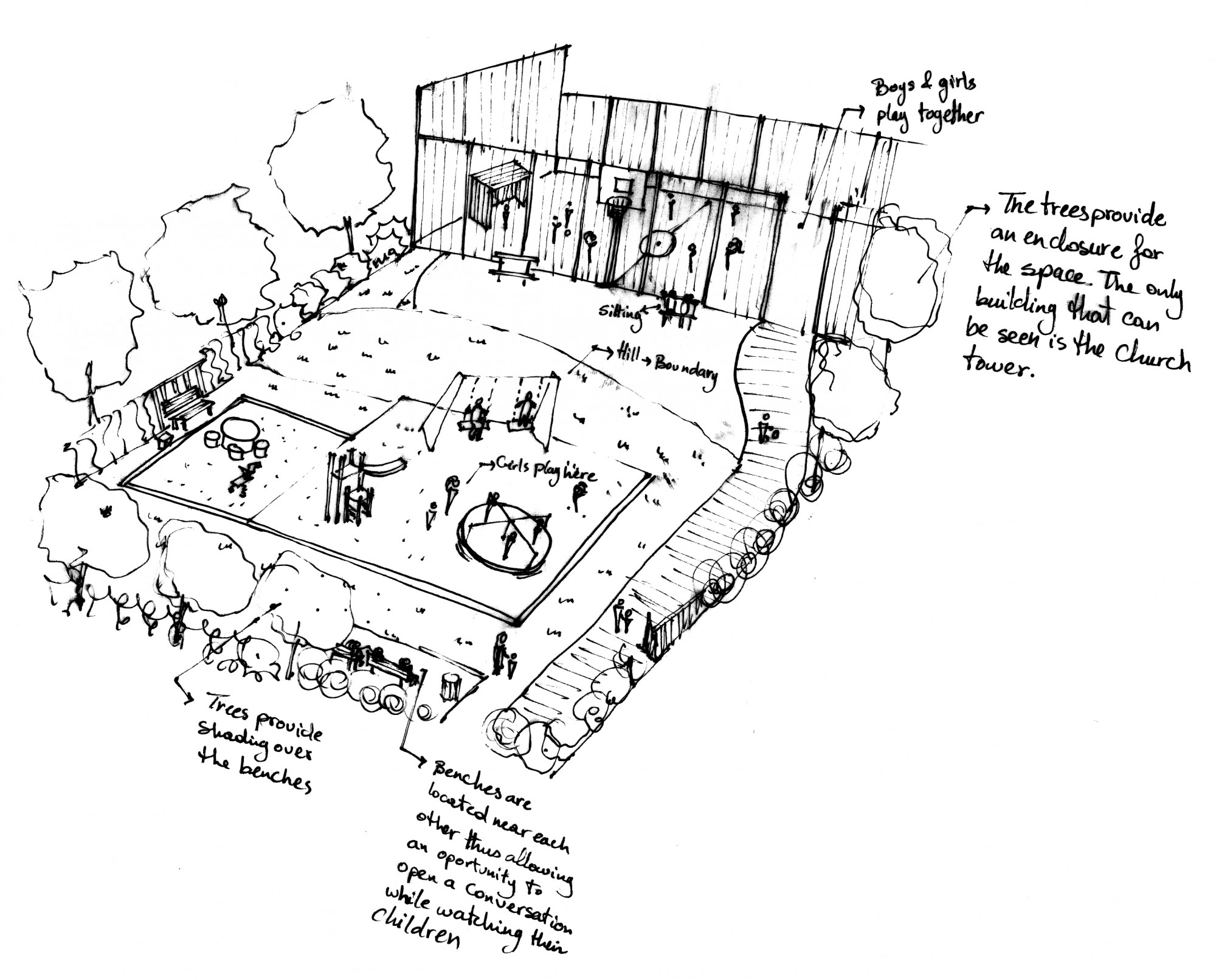

At the local playground children are gathering and playing together. This practice produces stories that are shared: The local playground figures as a place that allows people from different age groups and nationalities to gather. [Collective Spaces]

Meeting Neighbourhood-Insiders

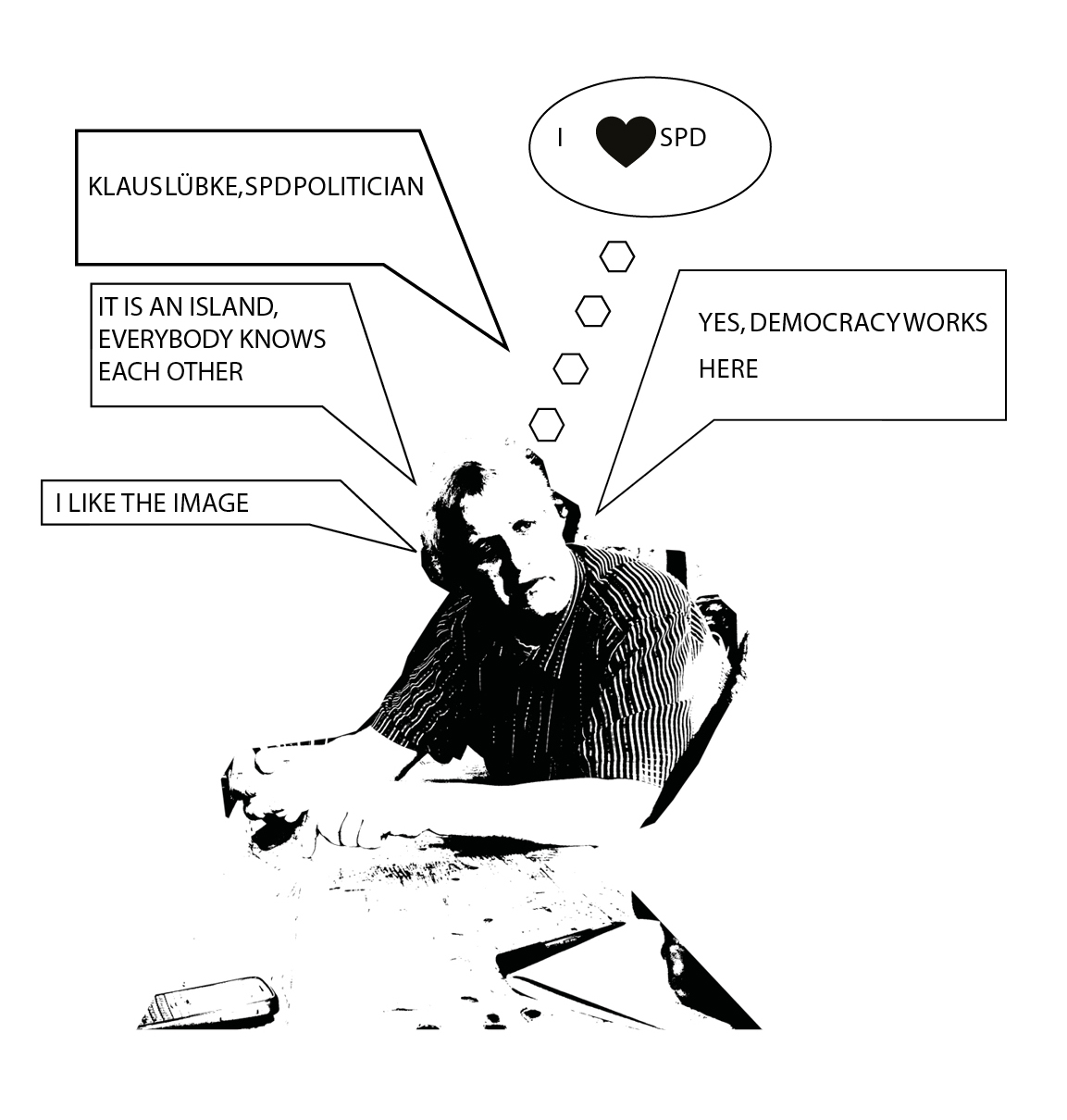

Who can we ask in order to learn more about neighbourhoods and their inhabitants; and how can we analyse and understand the neighbourhood’s constitution and composition within the context of the entire city? Often, scientific reports focus on neighbourhoods’ social and cultural compositions and their economic potentials or challenges and make these data available, but the ‘neighbourhood voices’ and their local expertise remain marginalised and do not find their way into these reports. This is especially problematic as it excludes local knowledge and close insights of both resident-experts and professionals or activists of local NGOs or political parties who live in the area that would be of potential use to those studying and understanding the area. When studying neighbourhoods, neighbours are our experts.

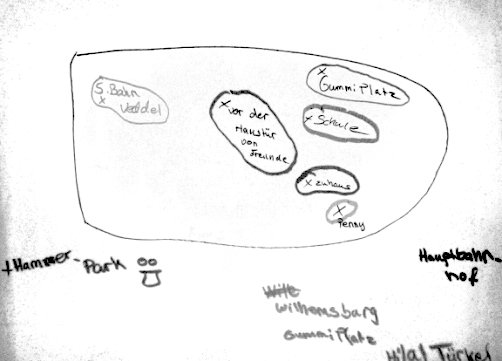

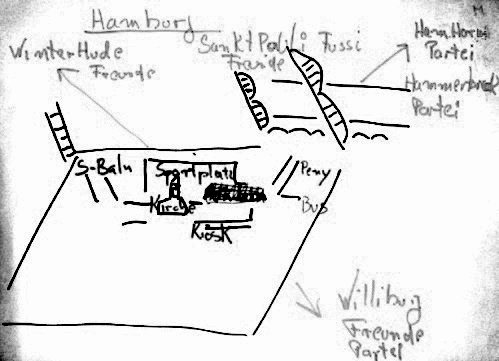

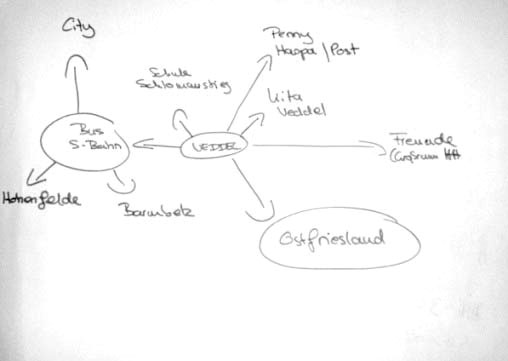

Mental Mapping

For purposes of documentation we also took photographs and annotated the maps, linking the photos to the map by indicating where photos were taken and what they showed. In the research process, we integrated these maps and layered them so as to produce a dense collection of mapped data. Analysing these maps helped us to weave the various aspects we had studied together. Our final presentation demonstrated how we layered and dissected these maps by using text, graphics, sketches, photos and perceptions. [Threshold]

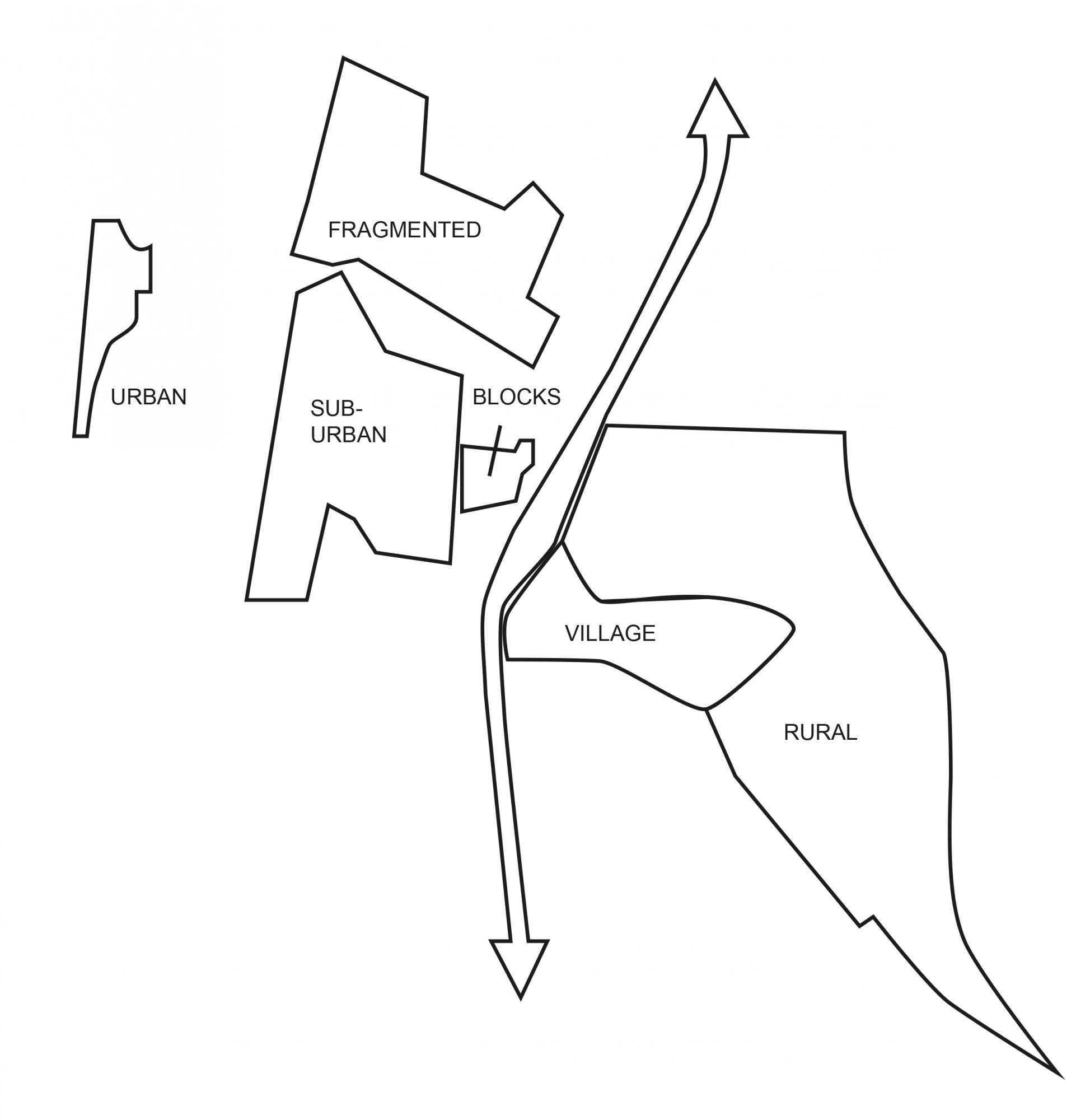

»We are an island - in Hamburg. You have to imagine that. If we get rid of the bridges, we’d have our own land here. We could totally take it over. There are only two entrances, over the bridges. It’s like a fortress.« Veddel resident

Mapping

and places for gatherings in a catalogue

that distinguished between ‘institutions’ as collective places, such as the church and the mosque, and ‘People‘s Places’ which were named during the local street festival. This catalogue provided us with information about the places’ qualities, accessibility and target groups and, combined with the residents‘ choice, a focus on one place that we decided to focus on in our working group. [Collective Spaces]

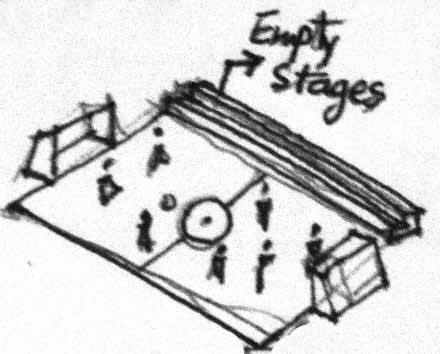

Islands within the island. Different parts of the Wilhelmsburg river island and transport infrastructure as a central barrier. [Traffic & Trade]

»Veddelers are aware that outsiders refer to the Veddel as a ghetto. Some groups, especially young men, playfully integrate this label into their identity. The cultural borders are mostly crossed by children while the German community feels frustrated as a minority, treating migrants as invaders and some non-German Veddelers feel that these are Germans who do not want to integrate into today’s Veddel. Graffiti appears as ‘communication‘ facade in certain assigned places.« Yiannis Pappas

Interview

Interviews presented another method we used. They were employed for two different purposes and in different stages of the research. The first purpose the interviews served was to get access to key people (gatekeepers) and topics concerning the neighbourhood. We interviewed Dr. Francine Lammar, a social worker who runs the ‘Veddel Aktiv’ organisation. In this interview, we asked open questions and invited the interviewee to present their own perspective – as opposed to asking specific questions in order to gather data on specific aspects. We therefore considered this type of interview as another type of experiential activity. The information we gathered from this interview contributed to shaping our ideas and helped us formulate our research interest more specifically. We then wanted to validate and complement this initial information, which is why we also used a different interviewing technique. With this second type of interviews we were able to focus more on specific questions and topics such as habits, rituals and ethnic relations. While interviews are useful, they are not sufficient and need to be complemented with other methods of data collection and research practice. Interviews have a caveat in that they present narratives and issues that are of interest to the interviewees and do not necessarily cover the researchers’ interest. Interviewees can also withhold information, both purposefully and unintended. Semi-structured interviews also follow a set of questions that may be useful to gain some aspects while missing out on other pieces of information that could have been useful. [Threshold]

Our interlocutor was Mr Özden Kaya, a longtime resident of the Veddel of Turkish origin. Besides giving us a lot of useful information about the neighbourhood, Mr Kaya helped us to define our research interest insofar as some of his expressions appeared to be in stark contrast to what another Veddel ‘insider’ and local activist, Dr. Francine Lammar, had told us earlier concerning the mobility patterns of Veddel residents. Such contrasting views illuminated how different people have different perspectives and make different experiences – even when concerned with the same topic. [Traffic & Trade]

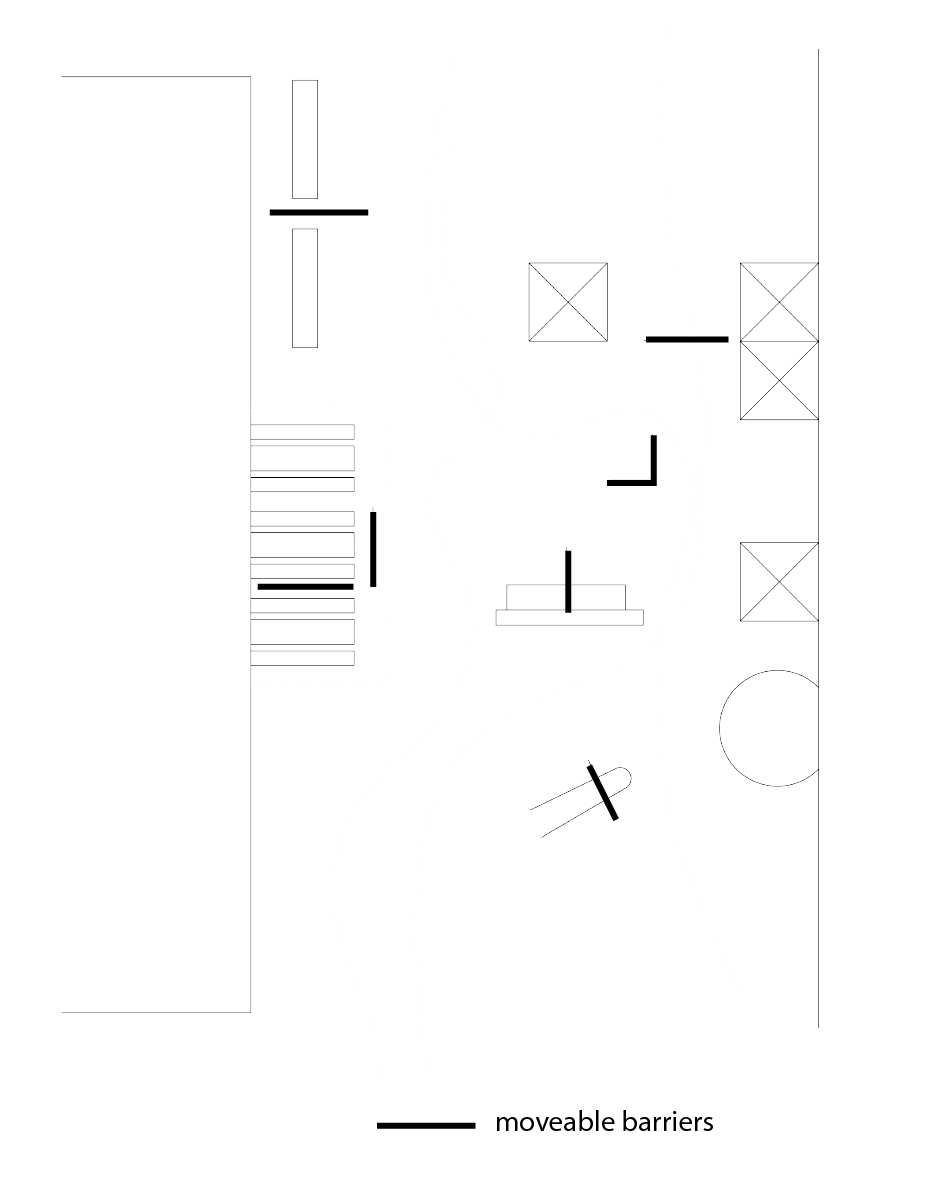

As we continued our observations and gained a deeper understanding from the Veddel interviews, we realised the considerable social and cultural divide within the neighbourhood as well as its effects. This was quite apparent in the public domain as countless barriers and fences dissected public spaces. [Barrier]

»Veddel used to be a dirty and dangerous place because of the drugs but this has changed (…). Even if our neighbourhood is an island it doesn’t represent itself in terms of an isolated space and that‘s mostly because of the good transportation by S-Bahn and buses. I have a car and I can easily commute everywhere. But I believe that mostly for children and for young people Veddel is a socially restricted place. I have four kids, they are able to speak German, Greek, Turkish and English. But they believe that the Turkish language is the most useful of them all because it is by far the most common language spoken here. There are classes in kindergarten and in schools where there isn’t a single German child.« Worker/ Veddel resident

Working on the Wall

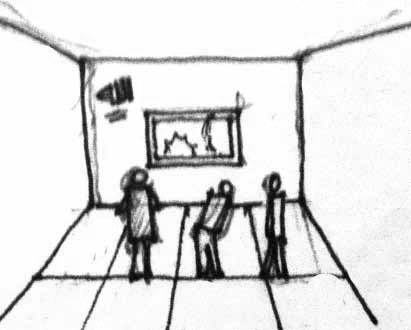

‘Make use of the wall; pin your work to the wall and present it!’ This has been a repeated slogan throughout both workshops. Participants collected various material, large amounts of information and drafts while observing, interviewing, mapping, drawing and reviewing the literature. One important question was therefore how to organise and communicate to others such multifaceted information without describing it piece by piece. How can such data generated in the research process, furthermore, be organised yet so that it remains flexible and adaptable to future findings and discussions? The groups therefore aimed to maintain a constant flow of generating, organising and discussing their data, allowing multiple interpretations and, importantly, re-interpretations. Participants were asked to pin their data to the walls in the UdN. Notes, drawings, photos, sketches, maps, found objects and the like covered the UdN walls. This meant that a hanging order as well as a narrative and a description had to be discussed among the groups, stimulating discussion and negotiation processes. By pinning collected information to the wall, their variety, dimensions and different focal points became visible to the other groups and teaching staff, resulting in productive discussions between groups as well as within groups. Following an open source principle, this method also allowed the working groups to use information among them, sharing data so as to use it in different projects and analyse it from different perspectives. Working on the wall by clustering information, identifying linkages and networks or demonstrating developments over time contributed to a common analysis of the neighbourhood and led to a deeper understanding of the specific research conditions and approaches. Later on, using the wall also helped to present research findings to a wider audience and opening the different perspectives onto the material, which allowed for discussions with external guests and neighbourhood residents.

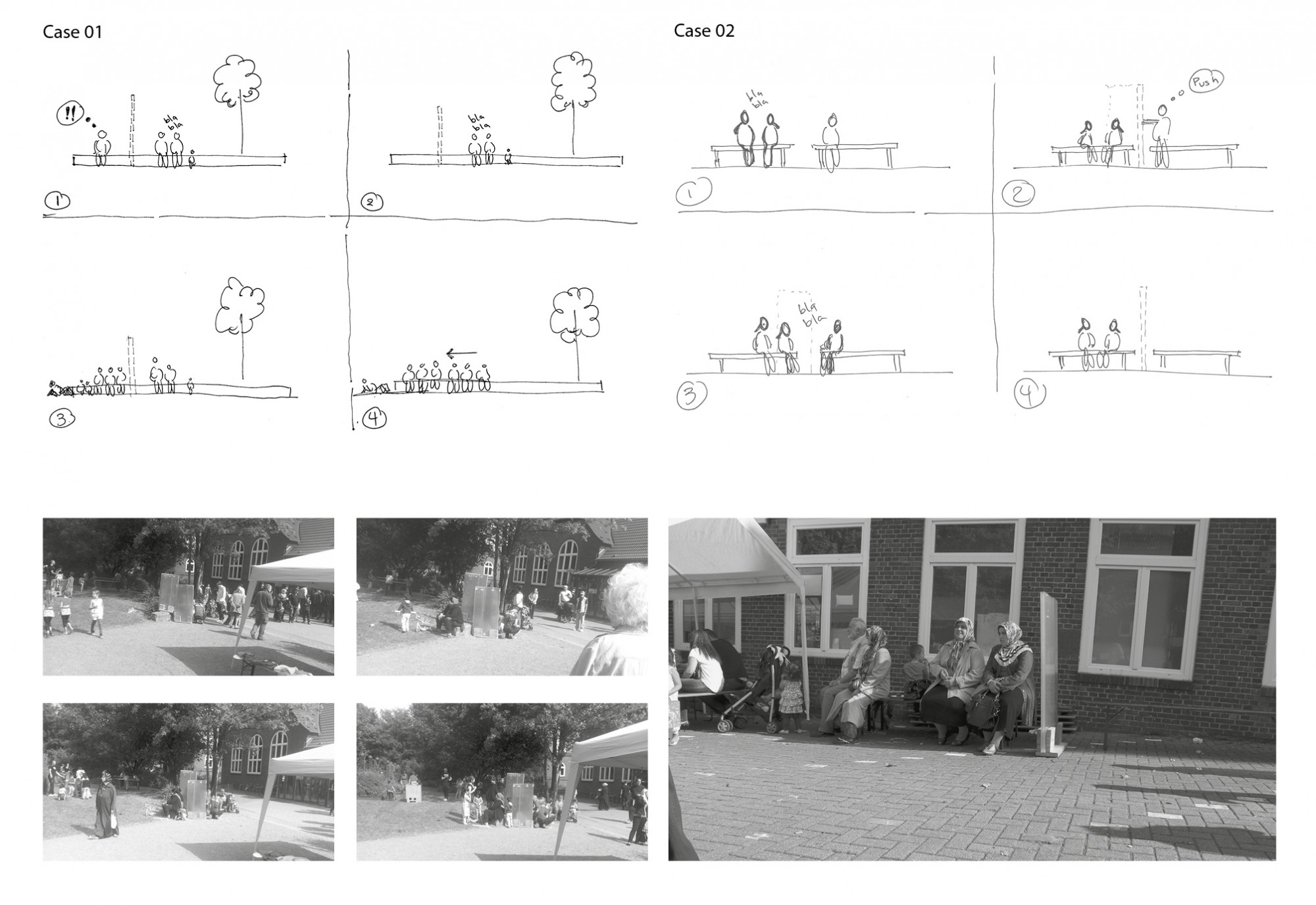

Intervention

Open Dialogue

The workshops were based on an understanding of research as permanent dialogue between researchers, research area and its inhabitants, as well as among the researchers themselves. This perspective underlines the role of communication and brings into focus the various communication strategies used between researchers and inhabitants as well as among researchers themselves. Communication became especially important in such an intercultural and interdisciplinary setting. Participants faced different communicative situations, such as debating and agreeing on methods and approaches with their fellow group members across various disciplines and backgrounds, talking to people in the neighbourhood in order to gain information, sharing information and findings with other groups and teaching staff, and not least reflecting on information they had gathered. In short, they had to work out a common language to work as a group, to process information they had gathered and to jointly develop a research question for further neighbourhood research.

Understanding research as a permanent dialogue between researchers, the area or subject and its inhabitants, but also between the researchers themselves meant that communication strategies were significantly important for the research process during the workshop. Researchers were put into different situations in which they had to communicate with each other or with others in order to gain information, share information or reflect what they had discovered. The had to communicate within their working groups and match different analytical tools and theoretical approaches according to their different disciplines. They had, in short, to find a common language to work with their material, to work with one another and to make themselves understood. This also required that they jointly developed an overarching research question for further neighbourhood research.

»Working in interdisciplinary teams has both advantages and disadvantages. One advantage is that you get to know how people from other fields think and that there is a big difference between how you perceive the situation and how the person next to you perceives it. And the problem is that sometimes there were these clashes: we as architects and urban planners, we want everything to be visualised in form of graphs, maps, drawings, but on the other side people from political science, sociology and philosophy are focussing more on the textual material.« Hebatullah Hendawy

Learning from Each Other & Sharing Knowledge

According to the open source principle, working groups have been asked to share their findings with other working groups, thus promoting the ideas of learning from each other and sharing the pool of bits of information that could be used to lead to refined questions, new interests and relate to other groups. Both data and findings were open to all groups. Where possible, findings were also discussed with external experts, stakeholders and residents from the neighbourhood so as to gain feedback and discuss quality and relevance of findings and interpretations. The approach was characterised by an iterative, circular process of data collection, discussion, analysis and interpretation. Sharing information according to the open source principle included developing the ability to communicate information and to enable sharing of a collective stock of information that could be read and used from various perspectives and angles. Following what symbolic interactionists such as Denzin proposed, research in its own right only made sense if it was communicated to others and, most importantly, to those it actually pertained to. Findings were therefore discussed with external experts and neighbours who were invited to comment on the work. The teams actively intended to produce work that was relevant to the neighbours themselves, whilst equally producing perspectives that opened up new possibilities.