Themes & Working Groups II: Place Making

Max Mütsch, Jean-Paul Olivier, Mazin Karim, Abeer Youness, Joanna Kusiak

The second leg of the workshop brought the ‘Barrier Group’ to Cairo. Upon arrival, we faced old and new issues. We struggled most with creating a group identity and finding a research topic to study place making and how it worked in the borough of Al Darb Al Ahmar. Finally, we found ourselves on Midan al Batneyya Square and decided to look into the question how the existing physical space influences the behaviour of its users.

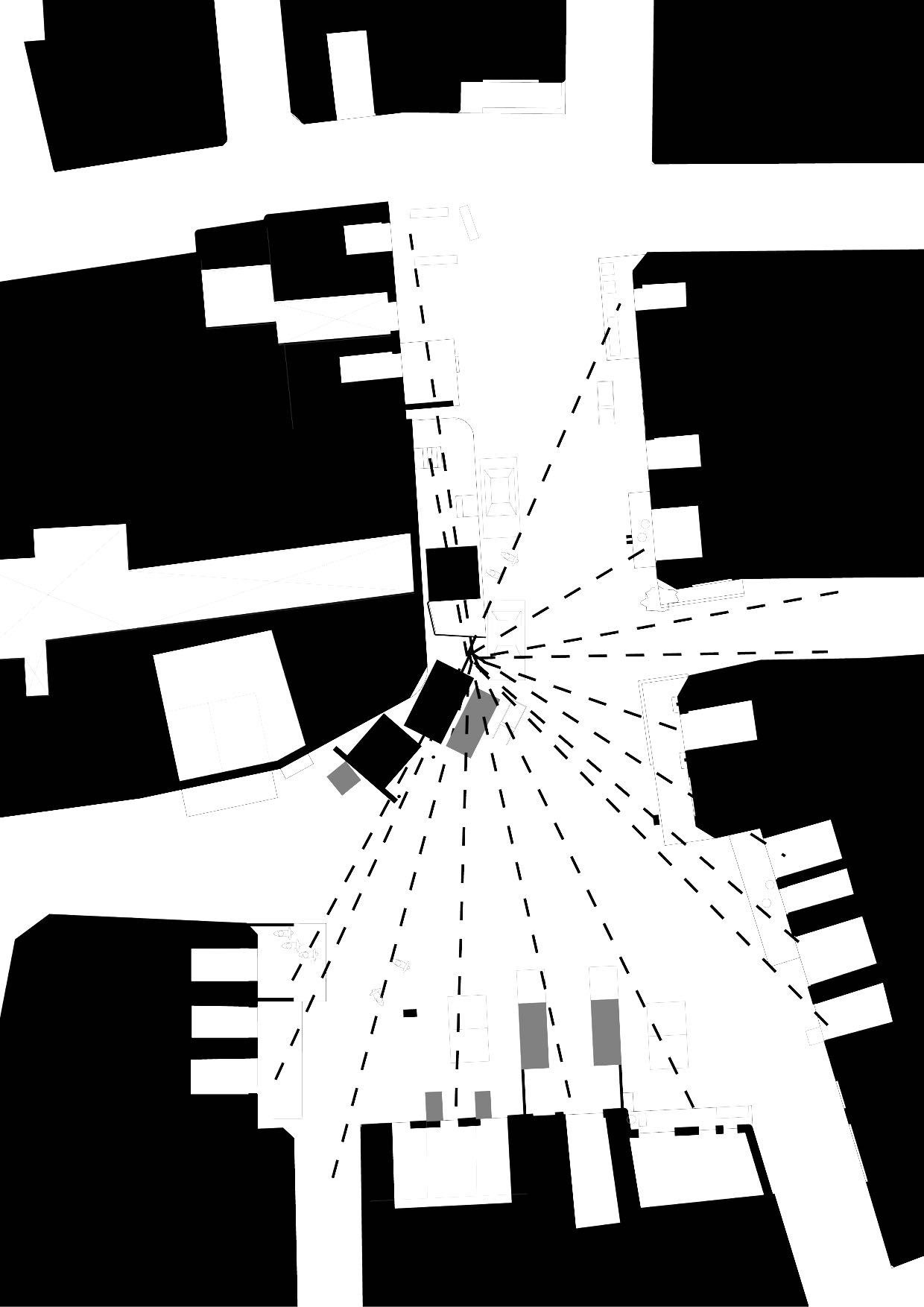

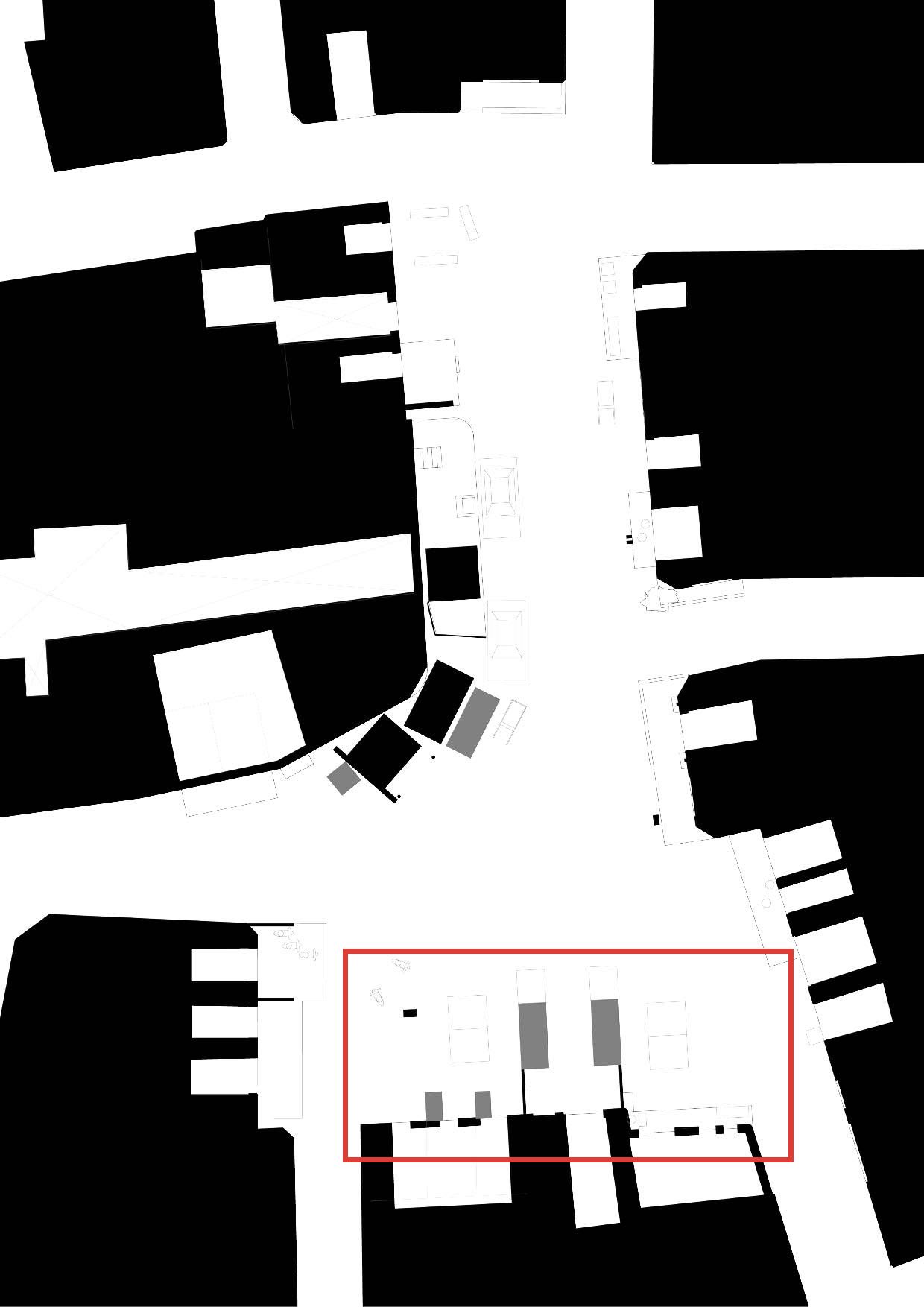

Mapping of activity setting

Different networks on Al Badneyya Square

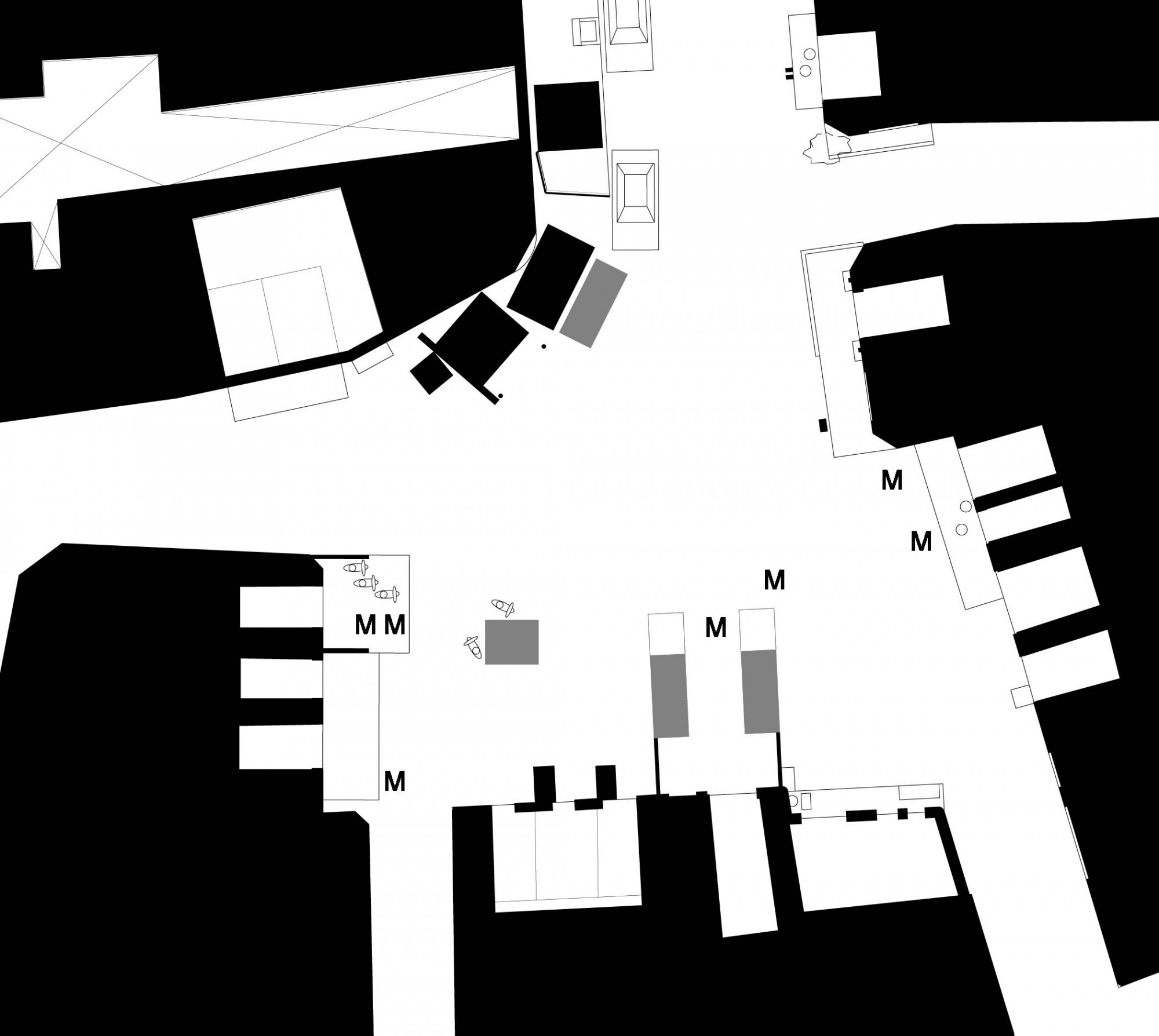

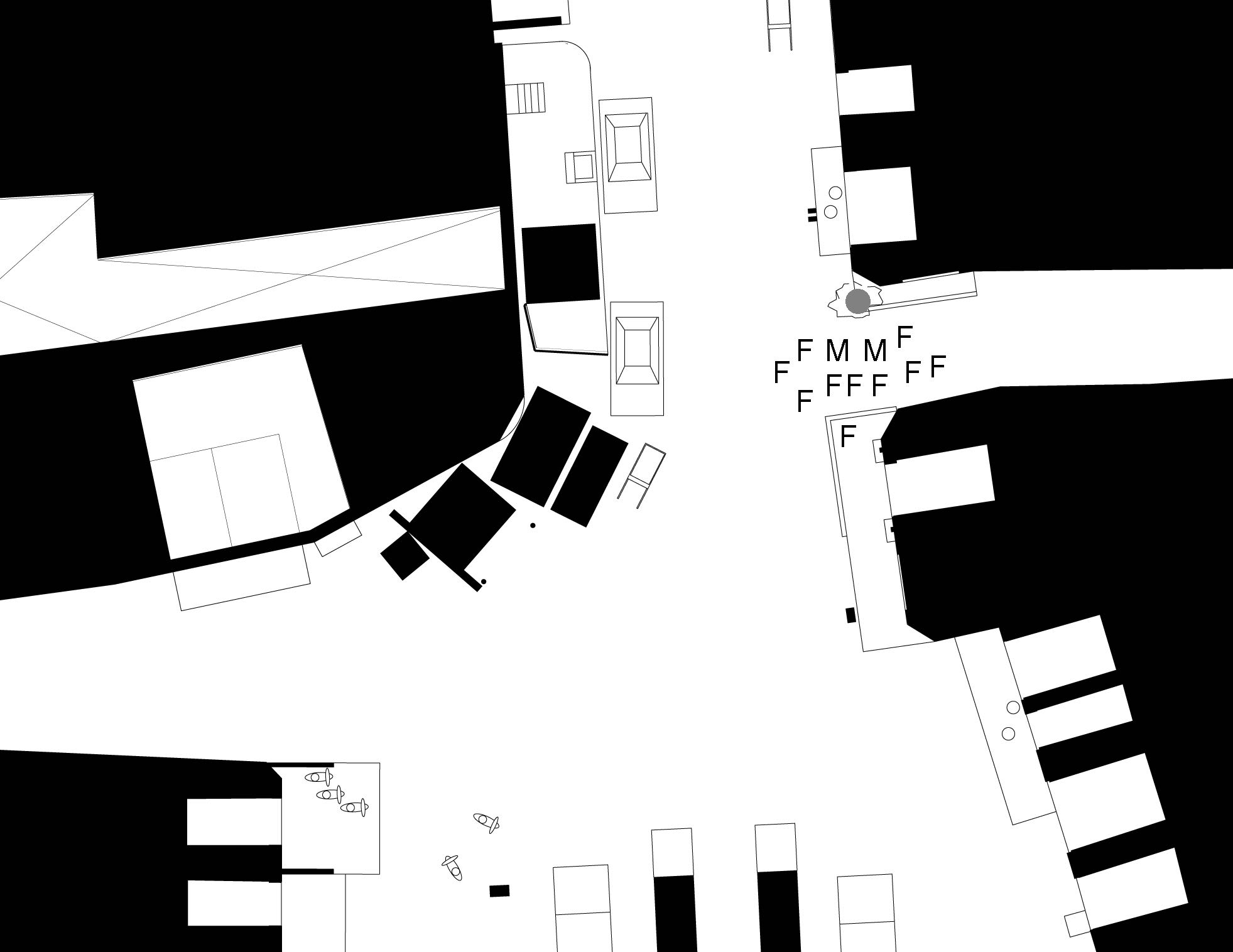

Catalogue of activity setting

Bread sales

The bread line is not blocking traffic and allows for social activity and mingling to occur.

Box storing

Creating spatial opportunities on both sides and disturbing the flow of traffic.

Trash collection point

Bread kiosk moves to another location. Cats and dogs occupy the garbage collection point. The enclosure is not suitable for children or recreational activity. Economic opportunities emerge for independent garbage collectors.

Recreational activity

Space is occupied by playing children. More women appear.

Notes from Al Batneyya Square

On Thursday at around 12:17, a local robabikya enters Al Batneyya Square from the left side carrying a tin bathtub on his cart as well as a white toilet bowl evenly covered with dust. We note this as meticulously as we note possibly everything that goes on on Al Batneyya Square. Robabikya is the name for a person collecting scrap metal, old clothes, slightly broken pieces of furniture and anything that can possibly be sold again. In terms of sustainable urbanism, robabikyas have always been on the forefront of the recycling movement, long before it became a middle class idea. A quick google search tell us that the word robabikya comes from roba vecchia, meaning ‘old clothes’ in Italian. On the big bazar under the highway bridge, we could probably buy the bathtub off this robabikya for 50 piastas. But more about this later. On Thursday at around 12:18, the robabikya looked at us when he passed us. Our eyes met for a moment and we knew that this was a moment of recognition.

Everyone on Al Batneyya Square knows our names already. They are not completely sure, however, about what we are actually doing. Sometimes we are sitting in one spot for hours barely without moving except for the odd waving the flies away. Only the robabikya knows that we are in fact (re)searching. What we call ethnographic research is not so far from his job. Like him, we go to the places that are thick of people’s daily lives and try to pick whatever is left on the street from their daily hustle and bustle, from their family affairs and business struggles. We collect whatever oddments we can find of the lives lived in Al Darb Al Ahmar, hoping to resell them later in the form of hypotheses or findings, relating to theoretical considerations. Our standstill is in fact a sign of our hunt, sitting still we are in fact trying to follow where these three boxes come from and why someone has put them close to the empty kiosk. Before she disappears inside the house entrance, our gazes follow a young mother with shopping bags. Seemingly bored, we are in fact agog to see the outcome of a minor street fight.

And when there is nothing more to pick up from the surface of urban life, we approach residents, similar to the robabikya who’s shouting underneath people’s windows, convincing them that we are happy with anything they can give us, even if they think it is a ridiculous piece of scrap. Whatever spare time they can find between work, we gladly accept it to ask our questions. And we take in more than just their words. We collect the smile and the crowfeet on the face of a tea woman and secretly steal the reflection of her golden earrings that are telling us more about her status than she herself would like to admit. Our memories, supercharged like a wooden cart, try to take and keep as much as possible: an old wooden electricity box, now used as a barrier between the trash pile and a kiosk; iron scissors hanging on the wall of a kiosk and the way the seller uses them; a daily calculation of a bread seller. And oh, how happy we are when among the pile of stuff we find we discover something that may be of value for our research. Being a researcher really is about selling the findings to the reader. It is about making the reader pay attention to what we have discovered and are offering now.

So welcome, welcome to Egypt! Please stop and take a look at what we have to offer! There are some beautiful findings. You should buy the story, we can see that it suits you well. We give you a good price. A really good price, just because you came today with an Egyptian. But don’t haggle too much. Our stories are all handmade and it took us twelve days to weave them together. It’s a really good price, my friend. Today, especially for you, we have a story on offer about a very special urban gate we found on Al Batneyya.

A gate made of Coca Cola cases

If you ever wondered how global capitalism entered Al Batneyya Square, it was through this giant gate, assembled from colourful Coca Cola cases as if from Lego blocks. The truck delivering cokes arrives every day and rebuilds the gate anew. Empty cases are being replaced by full ones and the gate changes colours from red (Coca Cola) to blue (Pepsi), with some individual yellow cases with local lemonade, but these are nothing more than dots across the solid monochromatic construction. The shape may differ slightly every day, but the owner – let’s call him Mohammad – always makes sure that the construction remains within the wooden panels.

Mohammad is the main supplier of soda beverages to the whole of Al Darb Al Ahmar. He is clearly the most powerful person on the square. By looking at the way he maintains the gate made of boxes, you can gauge his relation to the residents. He appoints himself as a kind of manager, not only of the beverage business, but of the whole social space that Al Batneyya Square provides. He is the first one to greet and to check up on the strangers. He is open and hospitable to us, playing a role both before us and the people on the square: he makes sure that we know how important he is, while he equally ensures that others see he has international guests. He likes to show off a bit, showing us a glittery violet wallpaper, which he saw in the hotels in Saudi Arabia, sweet as the candy his wife offers us. We buy cans of Coca Cola and take pictures of ourselves holding them. Mohammad has another picture of people holding Coca Cola cans. This photo is obviously of great value to him and there is a touch of proud confidentiality in his voice when he shows it around. On the dusty Square Al Batneyya, some high Coca Cola officials from Turkey and Canada are holding cans in front of the colourful gate. The sparkling smiles on the picture make Mohammad smile. Even a bread seller woman remembers well the day they came, which turned into a big celebration. A banner of Coca Cola was solemnly hung across Al Batneyya Square.

Standing underneath this banner, Mohammad feels in charge. He makes sure that the traffic runs smoothly (for instance he told us to move from a stone we were sitting on when a car came, and he moved similarly when a boy on a motorbike approached), yet he also willingly tells us about his family and his trip to Saudi Arabia. He has spent a couple of years working as a driver for the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia, a job that he got through family connections and that allowed him to accumulate enough money to develop his business afterwards. Mohammad is well settled and well off and it is clear to us that he will not approve easily of any changes that might threaten his life as it is. Like the recent revolution. After the revolution, he says, everything got a bit out of control. There were some shortages of gasoline, which disabled the daily truck deliveries. And people do not comply with former regulations anymore. For example, they now build higher than the four stories that used to be the maximum height hitherto. We follow his pointing hand gesture and have to acknowledge that indeed, there are a lot of high-rise construction sites around. You might notice that his building is higher too, but then of course, he is a well-networked person who even had assistance from the municipality to renovate and expand his buildings.

Whenever trouble arises, Mohammad feels he is in charge to take initiative. He know all the shopkeepers around and in order to keep his business going well, he maintains connections with officials. When Al Azhar Park was transformed from a dump into a fancy urban park and it turned out that there was not enough water for the neighbourhood, he proposed that the neighbours use empty Coca Cola bottles as Molotov cocktails and destroy the park. The municipality, formerly unwilling to talk, then decided to build a second pump as an alternative water source. That’s at least how Mohammad sells the story to us, and while he is telling us the story, he observes his helpers out of the corner of his eyes, making sure that the gate is being rebuilt the right way.

If you buy our gate made of Coca cola cases, you may want to dig into the following research questions:

How are capitalism and economic power relations translated into the daily life of this neighbourhood?

How do the informal structures of leadership and local power emerge?

How does the fact that the main Coca Cola distributor is located at Al Batneyya Square influence the dynamics of the whole neighbourhood?

How are the flows of capital and goods organised?

Al Batneyya Square – two main actors

After a short field observation and some interviews, we focused our research on two people who play important roles in the daily life of the public square. Through them, we were able to probe deeper into the complex network which covered the area in question. One was a woman who sells bread, the other a soft drink distributor. Both had different influences on the square. Both were influenced in their activities in different ways by the physical characteristics of the place.

The bread seller for instance left her official trading place: a metal box she rented from the municipality. The box turned out to be too hot in the summer and too close to a public trash collection point – a local hatchery for insects. She thus decided on her own account to move across the street into a shadowy corner with less flies. Through details such as this we uncovered links and hierarchies between the different groups, institutions and actants organising and contributing to the daily life on the square.

Portrait El Hag Ahmed Zuhdy

Becoming a Coca Cola & Pepsi Distributor

Ahmed Zuhdy was born in Al Darb Al Ahmar in 1958. As a four-year old boy he started working in his father’s shop (probably a grocery store). At the age of 30, he left Egypt to work in Saudi Arabia. His father’s death forced Ahmed to return to Al Darb Al Ahmar where he took over the family business. We don’t know when he became a Coca Cola & Pepsi Distributor, but that he upgraded his father’s business into a major soft-drink selling point.

Family Situation

Together with his wife, Ahmed Zuhdy had three daughters and two sons. The daughters don’t live with their parents and thus seem to be married. The sons work as drink distributors in Zuhdy’s business. Ahmed Zuhdy is further related to Sahar Om Ibrahim at 2nd or 3rd degree.

Job Situation

Ahmed Zuhdy is proud to be a salesman within a global network and to be one of the largest drink distributor in Al Darb Al Ahmar. He sells his drinks to 120 local stores – in the summer about 500 cases a day, in the winter about half as many. He is well connected on a local – neighbourhood – as well as global – international corporation – level, as he demonstrates by showing us photos of other salesmen and special events organised by Coca Cola Egypt. When he buys a case of soft drinks, he gets two bottles for free. This deal gives him an advantage over other distributors and may be one reason why his warehouse is (probably) the biggest in the area. The drinks are delivered from a factory in Nasr City, 20 kilometres away from Al Darb Al Ahmar.

Zuhdy’s influence on Al Badneyya Square

It is said that Mr Zuhdy owns one of the biggest warehouses in the neighbourhood. Yet the logistics of his soft drinks business is spread across Al Badneyya Square. He says: ‘There are no rules for taking up space – as long as one doesn’t disturb the traffic.’ Contrary to his perspective, another neighbour on the square reported that Mr Zuhdy is stockpiling the cases for other reasons: The Coca Cola gate blocks other shop owners, which has led to some of them having to close down their businesses on the square. The empty shops have then been taken over by Mr Zuhdy on cheap leases.

Housing situation

Mr Zuhdy owns a two-storey house with a basement. He and his wife live in one apartment, the other is rented to foreign students (for which he receives a monthly rent of 1000 Egyptian Pounds). The house was in need of repair following the earthquake of 1992, an endeavour for which Mr Zuhdy received financial support from the Aga Khan Foundation. He renovated the house and built and extra storey on top of the house.

Clearly, Mr Zuhdy demonstrates business skills. Some neighbours, however, see in him a gangster on the housing market. His practices are described as follows: He searches for houses in poor condition, seeks out their owners and offers them other flats in better condition far outside of Cairo City. If they agree and he can buy the shabby houses, he refurbishes them quickly, while the former tenants or owners leave the neighbourhood and their networks. Since the revolution, the housing market is seen to be out of control by many. There is no housing regulation. Those with money determine where houses and flats are built – a profitable business in the face of the housing shortage. In the light of his own success and the many displacements, hardships and inequalities taking place around him, it seems cynical that Mr Zuhdy himself misses the ‘good times’ under Mubarrak. ‘Since the revolution everything got worse.’

Al Badneyya Square and its different users at different times:

Portrait Sahar Om Ibrahim

Mrs Sahar Om Ibrahim was born in the late 1940s in Al Darb Al Ahmar. She received her high school degree at the school of tourism. Her dream was to become a stewardess, but this dream was buried when she got married. Ironically, Mrs Ibrahim never travelled. She has had several jobs and since four years works as a bread seller, a job paid by the municipality.

Family situation

Mrs Ibrahim’s husband works in the security business. He has spent three years working in Libya. Together they have four children for whom they want to provide good education opportunities. Mrs Ibrahim and her children live in her mother’s house in Al Darb Al Ahmar. On weekends, she meets her husband outside the neighbourhood in their own flat and returns to Al Darb Al Ahmar during the week to work.

Job situation

Mrs Ibrahim is a breadseller on Al Bedneyya Square from Saturday to Thursday. Her work starts at 7am and ends at 3:30pm. She earns 200 to 400 Egyptian Pounds a month. She doesn’t only sell bread however, but plays an important role in the struggle against subsidised flour corruption. This system consists of different levels. On a local level, Mrs Ibrahim is the municipality’s representative. She receives ten special tickets, which allow her to buy bread from a bakery that uses subsidised flour for their bread. The bread is cheaper than bread made of regular flour. For each of the ten tickets she can buy 50 loafs of bread.

The municipality prescribes certain rules for Mrs Ibrahim: 1) no one is allowed to buy more than 5 loafs of bread on any one day (one loaf costs 0,2 Egyptian Pound). 2) She has to sell her bread out of a certain shop (a metal box which she has to buy from the municipality for 10,000 Egyptian Pounds) in a specific area (Al Badneyya Square).

Another level of the anti corruption system is the relation between Mrs Ibrahim , the delivery man and the bakery. Mrs Ibrahim gives one ticket to the delivery man. He passes it on to the bakery in exchange for 50 loafs of bread. He returns to Mrs Ibrahim who sells the bread. This supply chain is repeated at least every 15 minutes. When Mrs Ibrahim runs out of tickets, she gives him 100 Egyptian Pounds in return for the 10 tickets.

The municipality only pays Mrs Ibrahim. She receives no benefits from the sales of bread. And yet, she breaks the rules sometimes: a) sometimes all the 50 loafs of bread are sold at one time (for example at lunch time when construction workers send someone for their food, which means that other customers have to wait), b) some people are allowed to buy bread for about 1,5 Egyptian Pounds per head (very poor people as she says), c) she doesn’t sell from the metal box. This latter point is due to the fact that it gets too hot from the direct sun all day and that it is located right next to a trash collection point and contaminated with flies. She argues that she doesn’t want to sell unhealthy bread.

Mrs Ibrahim’s influence on Al Badneyya Square

Mrs Ibrahim is an important presence on the square. Even people from outside of Al Darb Al Ahmar come to visit her shop on the square to buy bread from her because she sells it at a cheap price. Sometimes, these customers then re-sell the bread a few corners down for a higher price. Where she sits – across from her metal box – under a tree in a street corner, she occupies a relevant spot where men and women are allowed to meet publicly.

Conclusion – Place Making

We started with material items that are used in the process of place making. These items – Coca Cola cans and bread – can be found everywhere, not least on the Veddel and in Al Darb Al Ahmar. And of course these products are not only used to create neighbourhoods. We understood them as an entry point to probe deeper into the complex networks that make the everyday function in neighbourhoods.

Al Badneyya Square and its different users at different times, here in relation to the spot where Mrs Ibrahim sells bread: