Themes & Working Groups I: Traffic & Trade

Felix Blass, Noel David Nicolaus, Salma Sherif

An island as transitional space

Research on the Veddel produced two topics within one day that proved rich in terms of their accessibility, their daily presence in both obvious and hidden ways as well as their meaning to residents in the neighbourhood. We realised that they are part of what makes the Veddel a unique place within the city of Hamburg. The first topic was observed during the dérive that served as a first approach to the field of research in a larger context and returned again and again in many ways: Wilhelmsburg as the biggest river island in Europe, fragmented again into smaller parts with their own character. The Veddel is an island that belongs to Wilhelmsburg but separated from the city through water, transport infrastructures and socioeconomic peculiarities. The second topic we came across on the first day was the logical counterpart to isolation that is usually associated with an island: connections. We observed these in terms of transport infrastructures connecting the island by car, train and bicycle routes, as reappearing signs and symbols in the public realm or, in much more abstract ways, as the cultural diversity that makes the Veddel and Wilhelmsburg a special place within Hamburg with connections to places far away.

In urbanist contexts, an island is often described in negative ways referring to missing social integration, low mobility and little access to a city’s common resources. One exception is the concept of the city of short distances that emerged in the 1960s out of the discussion around urban density fuelled by publications such as Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961). The concept of the city of short distances implied high density of usages within the urban fabric, providing an alternative to the functional segregation propagated by modernist prophets for decades at the time, and whose negative consequences became apparent in the shape of urban sprawl, increasing traffic and the resulting wasteful use of natural resources. It was the attempt to re-interpret as a strength the diversity and constriction of historical cities that had been rightfully criticized for their lack of health and sanitation and to rediscover an idea of urbanity that had been declared out of date and inefficient. Returning to the Veddel, two contradicting quotes from our initial conversations with experts and residents developed into our main focus: "Some people never get out of the Veddel." (Dr. Francine Lammar, Veddel Aktiv e.V.); "Everyone here has a car. Mobility is not an issue." (Özden Kaya, resident)

The contradictory nature of these affirmations caught our attention, leading us to focus on mobility as our main interest. Still, ‘mobility’ proved to be a very broad topic given the short amount of time available to conduct our research. In our group sessions, while brainstorming over our data, we found that the topic of insularity as well as the question whether ‘daily needs’ could be met on the island proved highly relevant for us. We also wanted to find a way to investigate how the perception of spaces in the neighbourhood changed depending on the social actors we would observe. We thus thought that it would be interesting to turn ‘insularity’ and the related assumptions about the closed spatial and social nature of the Veddel upside down, questioning the negative stigma attached to it and instead suggesting insularity as a positive quality, both in terms of sustainability and social cohesion. In other words, we wanted to conceptualise the Veddel as a small piece of the ‘city of short distances, a notion now popular among those planners and social actors advocating urban density as a means of dealing with sustainability issues.

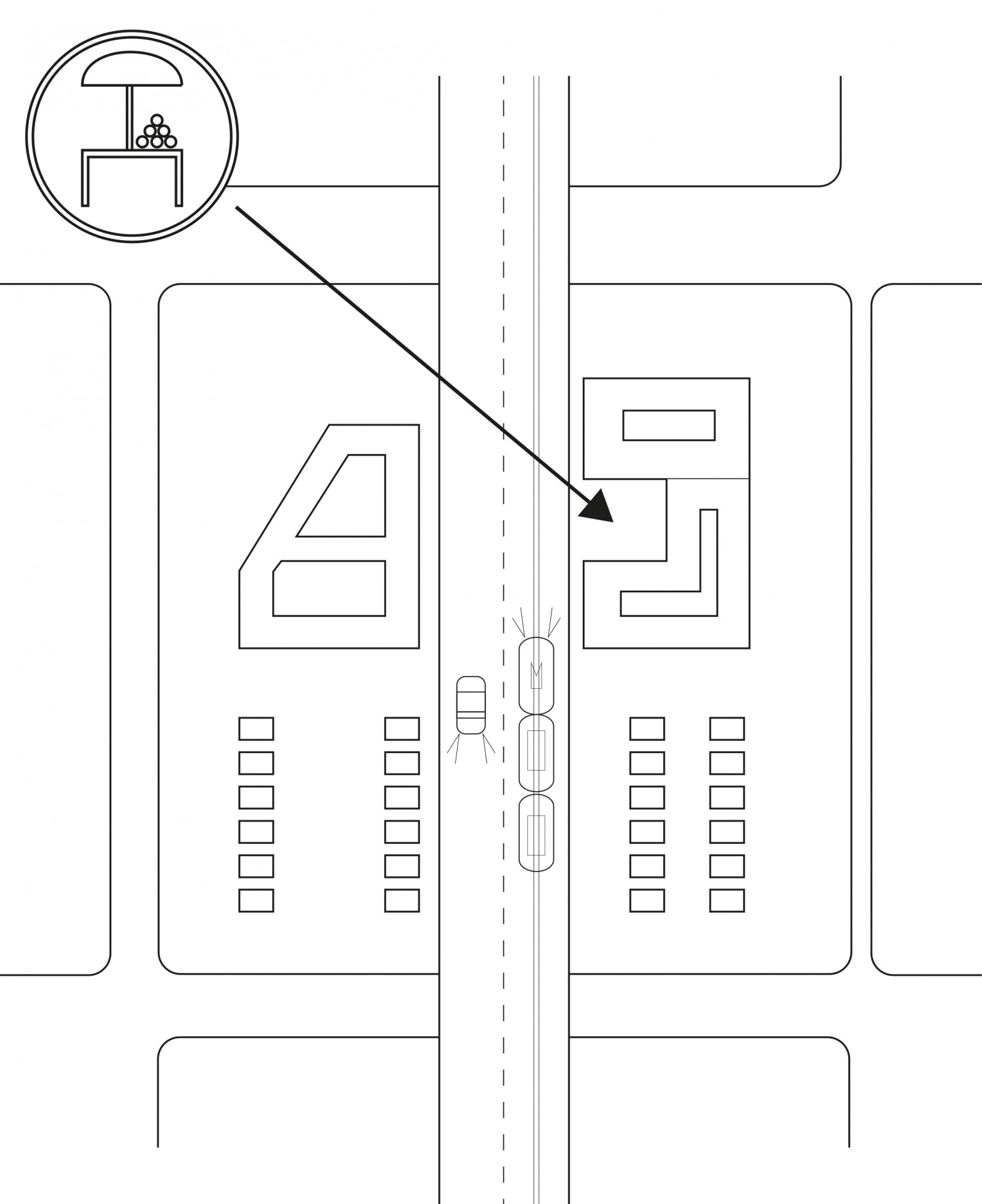

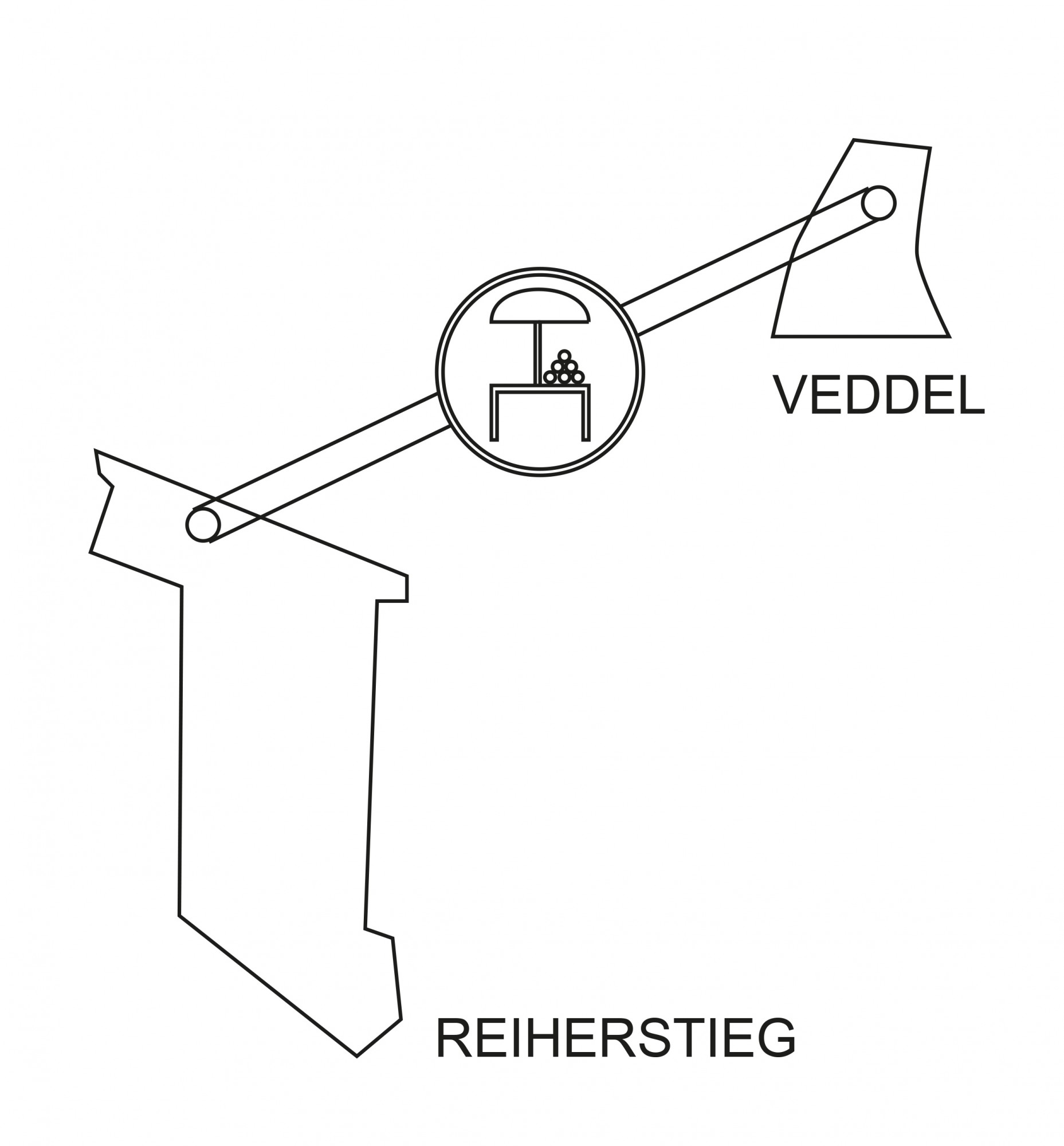

As a result of our efforts, we realized that mobility was indeed a major issue in the neighbourhood, if in a different way than we expected: local residents complained a lot that commercial infrastructure on the Veddel was weak, if not close to non-existent; therefore they would have to leave on a daily basis to get many of the things they needed. This contrasted with the historical situation we could find based on interviews and research into archive material, which portrayed a strong local commercial infrastructure as well as a lively farmers’ market in the 1960s and 1970s. Looking for an illustrative case study to represent our interests and findings so far, we decided to focus in more depth on the local farmers’ market. For the last days, we concentrated on researching further into the historical development of the market and the reasons for its disappearance. Equally focusing on the connection between the Veddel and a market located outside the neighbourhood (more precisely the weekly farmers’ market taking place at Stübenplatz, in the neighbourhood called Reiherstiegviertel), findings from the mental maps and various conversations indicated that some kind of functional replacement between the old market located on the Veddel and this other, already existing external market had occurred. A diachronic perspective on the Veddel’s development clearly showed that the neighbourhood which was constructed as a residential area for workers from the adjoining industrial compounds (mainly located on the Peute island) had lost its original functions as an ‘integrated neighbourhood’, as it had originally been intended by the influential turn-of-the-century Hamburg architect and city planner Fritz Schumacher. Still, historical documentation retrieved from the ‘Veddel Aktiv e.V.’ suggests that until the big flood of 1962 a strong local commercial infrastructure existed on the island. In the aftermath of the flood and during the subsequent exchange in local population structures, which saw a strong inflow of Turkish immigrants replacing the aging German population over the course of a decade, many shops changed ownership and started to cater for the needs of the Turkish population, mainly ‘ethnic’ grocery stores. Today, just one such store remains, and the vacancy rate of retail space, though not as high as a decade ago, is still considerable. Our question was thus: What had happened in the meantime that had weakened the local retail infrastructure so much?

Although due to time constraints we couldn’t focus on the influx of more complex factors, such as the general change in consumption patterns in urban areas during the past decades or the specific role of a decrease in local purchasing power due to population exchange, the weak retail infrastructure appeared to be related to the development of the local mobility infrastructure. This became visible while concentrating on the local market place. Focusing on the local farmers’ market, we found a strongly symbolic space not only epitomising the development of the neighbourhood as a whole but equally functioning as an indicator for the changing fortunes of the local commercial infrastructure. Founded shortly after the beginning of the island’s urbanisation in the wake of the Harbour’s industrialization, the market was located in a square (actually called ‘market square’) characterized by typical Wilhelminian housing blocks. While the square and the surrounding buildings had been obliterated during the Second World War air raids, the Schumacher housing blocks were mostly spared or reconstructed after the war and until today characterise the island’s appearance.

As a typical example of post-war urban development, the historic square was replaced by a highway interchange. Still, the market continued to take place and was moved to the nearby Slomanstraße. Here, it continued to function and serve the neighbourhood until its demise during the first decade of the 2000s. From that point on, residents of the Veddel had to use other farmers’ markets on the island of Wilhelmsburg. To understand the relationship between mobility and commercial infrastructure, one should keep in mind the fact that the Veddel can be considered the ‘entrance’ to the city of Hamburg when coming from the southern shore of the harbour. It is, and was, an important transit point. But while historically the roads to the proper city core had always crossed the neighbourhood, cutting through the urban fabric, the main flows of traffic were restructured during the past decades so that they now bypass the neighbourhood. The last development in this sense was the pedestrianisation of the main street of the Veddel, the Brückenstrasse, which followed the removal of the tramline and the construction of the highway. In other words, the heavy traffic flows entering Hamburg now bypass the residential area at high speed, without entering the actual neighbourhood. This development, together with the strong decrease in overall population numbers (which are now halved compared to their peak: from 10,000 to less then 5,000 inhabitants) and the reduction in purchasing power following the influx of immigrant populations, are reasonable elements to suppose that the overall purchase power of the island decreased to such an extent that it could no longer sustain a large commercial infrastructure nor a weekly market.